vi-rus [vahy-ru,s]

1. an ultramicroscopic (20 to 300 nm in diameter), metabolically inert, infectious agent that replicates only within the cells of living hosts, mainly bacteria, plants, and animals: composed of an RNA or DNA core, a protein coat, and, in more complex types, a surrounding envelope.

2. Informal. a viral disease.

3. a corrupting influence on morals or the intellect; poison.

4. a segment of self-replicating code planted illegally in a computer program, often to damage or shut down a system or network.

mar-ket-ing [mahr-ki-ting]

1. the act of buying or selling in a market.

2. the total of activities involved in the transfer of goods from the producer or seller to the consumer or buyer, including advertising, shipping, storing, and selling.

Yesterday I was discussing promotional plans with one of my authors, when he said something that really touched a nerve. What he said, in so many words, is that any time a corporation puts money into viral marketing, it will fail. After hanging up I thought about this, whether what he said was true, and whether putting promotional money behind a concept like viral marketing was simply contradictory by nature.

He said while a corporation's first instinct might be to throw $100,000 behind one piece of a viral marketing plan, they would be infinitely more successful by spending $5 on a thousand different pieces.

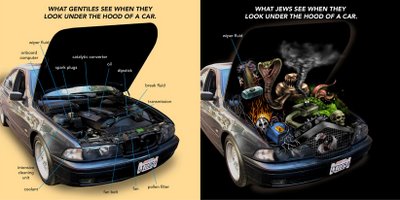

When I think of viral marketing, I think of funny emails and links forwarded to friends and colleagues. I think of organic material that reaches a tipping point and takes on a life of its own. I think of it as something that can't be planned or pencilled into a marketing budget, where there's really no rational explanation for its popularity or success. But is that really fair? And is it true?

Not in all cases. A few years ago, Little, Brown published a book called YIDDISH WITH DICK AND JANE. It was a parody on the popular grade school primers, and to promote it, Little, Brown commissioned something called a VidLit, a short promotional video for the book which would ostensibly be forwarded around the internet and persuade people to pick up the book. At the time, VidLit was a relatively new tool, and when the VidLit for YIDDISH WITH DICK AND JANE premiered on the internet, it was passed around like a bong at Silent Bob's house. It spurred massive sales for the book, which sold out its first printing in about 3.5 minutes, and has since sold nearly 200,000 copies. The book likely would not have been as successful without the VidLit, and needless to say others began to copy the model.

After the success of the YIDDISH VidLit, the tool was overused and dulled worse than a three-week old shaving razor. Because YIDDISH was a high concept humor book whose audience was very much in tune with the internet, the promotion worked. I remember seeing the trailer and sending around the link to at least half a dozen people. But soon VidLits began popping up for every kind of book imaginable, from chick lit to mysteries to business. VidLits were created and aimed for audiences who, let's face it, weren't exactly the kind of book buyers who send around internet videos to their friends. If somebody sends you a funny link once in a blue moon, you're happy to pass it around. If they send you a new link every other day, eventually the task will get wearisome. Many of the VidLits I've seen are incredibly clever and well-made, but I don't think they've had nearly the impact as the beta models.

For an example of what sounds like good out-of-the-box viral marketing, check out Atria's promotion for Diane Setterfeld's THE THIRTEENTH TALE (which offers a special leather-bound copy of the book to bloggers who link to the contest. Of course I'm only mentioning this out of journalistic integrity. I hate leather.). I'm thrilled that publishers are taking more time to embrace the powers of internet and viral marketing, but what my author said makes some sense. You never want to be the last on the bandwagon--you want to build it yourself.

My author forwarded me this video, which is a parody of what happens when a company "overmarkets" a product. It's pretty funny and a little too accurate, and shows how easy it is to take something unique and make it bland. Promotion is a very reactionary type of business. As soon as something becomes popular (i.e. YouTube, MySpace) everyone looks to promote their product on it. So by the time "corporate money" is thrown at it, the fad is already either dying or oversatured to the point where it's impossible to get noticed. Two years ago VidLits were revolutionary. Today they're fairly common. It's a lot easier to stand out when you're one of one than when you're one of fifty. The trick for viral marketing, it seems, is to be the first one at the party and gorge yourself on the goodies.

Otherwise, in the great words of Milton (Milton Waddams, not John Milton), "The people to cake ratio is too high."